The Circular Economy (CE) is a phrase arising out of the work of Walter R Stahel, an architect who, in a paper from 1982 titled ‘The Product Life Factor’ first described a model for a closed-loop economy which is more commonly referred to now as a circular economy.

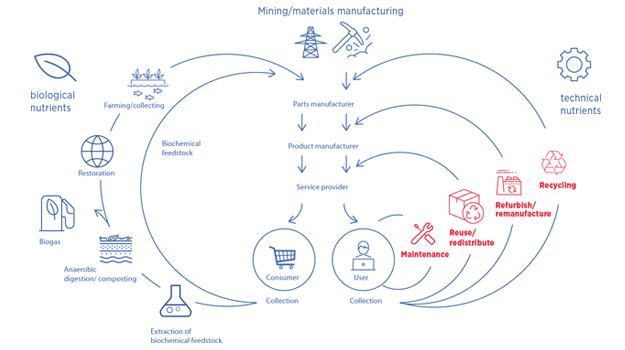

Above: Continuous flow of technical and biological materials through the ‘value circle’, courtesy of the Ellen McArthur Foundation

The Circular Economy (CE) is a phrase arising out of the work of Walter R Stahel, an architect who, in a paper from 1982 titled ‘The Product Life Factor’ first described a model for a closed-loop economy which is more commonly referred to now as a circular economy.

In what must have seemed at the time to have been a rather atavistic point of view, he suggested that extending a product’s useful lifespan would reduce resource depletion and lessen waste.

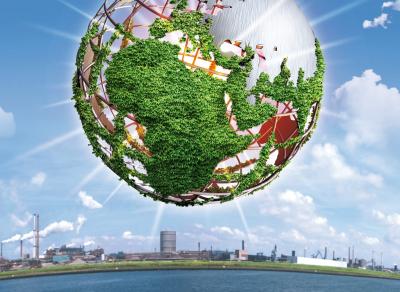

Circular Economic thinking extends this model further and considers the end-of-life options for all types of goods, both manufactured and, in the case of foodstuffs for example, grown.

Thus we have another well used aphorism; Cradle to Cradle, which neatly summarises the process whereby the waste from one process becomes the feedstock or raw material for another process.

Much work has been undertaken in further expanding thinking on the mechanisms which must be in-place to support the circular economy, notably by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, instigated by the yachtswoman after her many solo voyages revealed – in a very direct fashion – the need to conserve finite resources as a matter of survival. The report ‘Towards the Circular Economy’ produced by the foundation and McKinsey and Co is a seminal work in the field.

Circular Economics and cradle to cradle manufacturing require a major shift in thinking about how we use – and also, importantly, how we ‘own’ things. This is because the model relies on us reconsidering the accepted paradigm where, if something breaks we get a new one or if something is old we change it for a newer model. In the circular economy, whilst this might still be possible the original artefact would have an established end-of-life route.

The circular economy is built around principles outlined below, and the idea that ‘Nutrient streams’ exist for all processes and these can often arise from other industries or sectors’ waste materials, arisings and old and obsolete end products.

Nutrients are described as ‘Biological’ such as food waste for example or ‘Technological’ – the class into which steel would fall.

Waste = food. In the Circular Economics there is no such thing as waste.

Everything (within reason) can be re-purposed, re-manufactured or recycled in another process. It might emerge ostensibly unchanged – imagine renting – rather than purchasing outright – a dishwasher. It is rented for a designated number of wash cycles and then returned to the manufacturer for refurbishment, re-manufacturing or recycling into other processes. Almost everything we own or use on a daily basis could be procured and managed using this model which could be further enhanced by new and emerging technologies such as the internet of things.

Steel

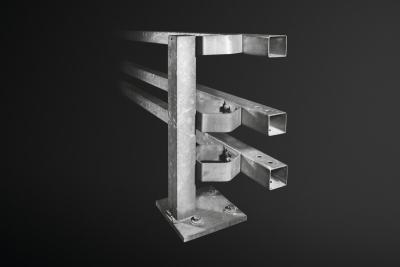

The steel supply chain is a good example of a circular economic model in microcosm. Because of its inherent value and certain properties that facilitate recovery from waste (such as being attracted to a magnet), steel and ferrous metals have been recycled for a long time. The circular economic model of steel is therefore well established and quite efficient (in some areas up to 98% of steel is recycled). Thus we can say, with more than relative certainty, that very little iron and steel goes to landfill. Most of it, if it is recoverable will be recycled, and the most common form of steel recycling is for it to become feedstock to the Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) or Basic Oxygen Steelmaking (BOS) process.

As resource and energy scarcity are bound to become more pressing problems in the future so the need to understand the integration of different circular models and how they are inter-related or inter-dependent will become more important also. In construction this might be issues around the improved recovery and re-use of materials, metals, aggregates, insulation, and plastics and glass for instance, and in addition how these operations integrate with existing socio-economic models.

Long life – loose fit.

Things, be they consumer goods or built infrastructure need to be constructed to last, to be adaptable and repairable. The premise here is that a consumer’s connection to the artefact needs to be ‘Emotionally Durable’ to increase attachment and therefore the likelihood that an item will be kept because of or despiteits patina, dents, scratches and other signs of use or age. This is interesting because of the potential ways in which products could interact with consumers in an active fashion, using web connectivity and the internet of things for example. In this world giving your car a name makes perfect sense.

Such thinking is quite easy to imagine with smaller objects – but thinking fondly of your office building or factory might be a bigger leap – unless of course such emotional attachment was celebrated and encouraged by design – as it was understood in an equally sophisticated way by the Victorian philanthropists who wanted passers-by and recipients of their largesse to understand instantaneously that this building was built to last by someone who cared about it, and, importantly, who cared about their legacy and how it would be perceived in the future.

This care percolated through from client to architect and engineer, to joiner, mason and bricklayer and represents perhaps one of the most convincing arguments for spending money wisely on good materials and workmanship.

And that, coupled with a mechanism for reusing and recycling everything, is the very essence of the circular economy.